August 05, 2019

By Blog Team

In

When it comes to translated fiction, Nordic Noir has been one of the biggest literary trends of the past twenty years thanks to authors such as Jo Nesbo and Stieg Larsson, whose best-selling Millennium trilogy has been adapted into several movies in Swedish and English.

Its popularity suggests that English-speaking readers have no reservations about reading books that have been previously published in other languages.

But could they be just as receptive to Chinese fantasy kung-fu novels, predicted by some in the publishing world to be the next big thing in translated fiction?

Revolutionary roots

Wuxia, as this particular genre is called, has been around in China for millennia, coming to prominence after the May Fourth Movement of 1919 when students in Beijing protested against the perceived weakness of their government. From this emerged a new fantasy genre - one that routinely featured a kung fu-fighting protagonist who stood for personal freedom and a rejection of the Chinese family system.

The word wuxia is a combination of the words “wu”, (meaning “martial” or “military”) and “xi” (meaning “chivalrous”, “vigilante” or “hero”). Banned at various times during the Chinese Republican era (1912-1949), wuxia has seen its growth stifled in China. However it did enjoy success in other Chinese-speaking regions such as Hong Kong and Taiwan.

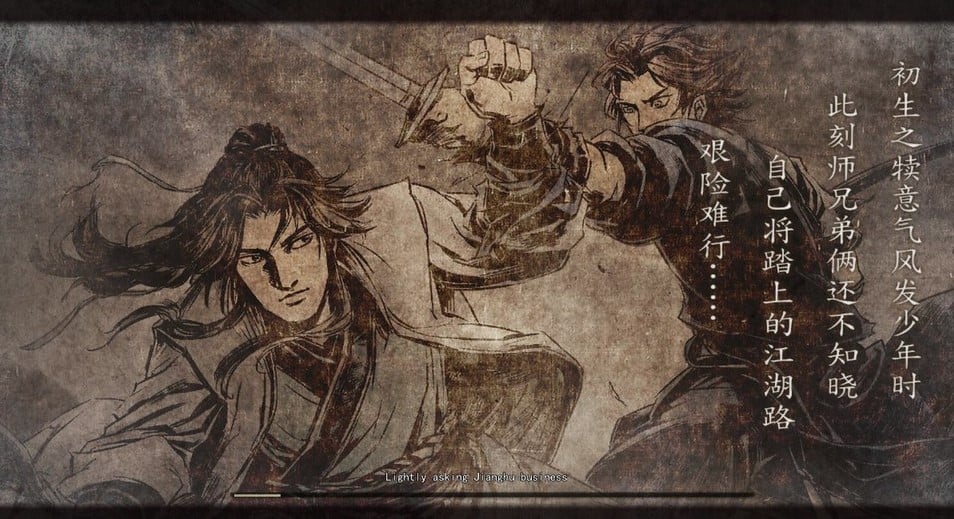

A typical wuxia story is set in ancient or pre-modern China and features fantasy elements such as magic powers and supernatural beings. Though its roots are in the written word, the genre has inevitably spread to other art forms, from movies to video games. And due to its universal themes of loyalty, courage and justice it has seen its appeal spread around the world.

Even the fact that some titles run to over a thousand chapters hasn’t dimmed its appeal.

Making inroads

Western cinemagoers will already be familiar with wuxia-influenced films like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Kill Bill. However as a literary genre it is less well known.

But things are changing. At this year’s London Book Fair in March, the media reported an increased interest in translated works among British readers, with a special mention of the wider acceptance of translated Chinese titles the year before.

Speaking to the Telegraph’s ‘China Watch’ section, Anna Holmwood, a literary translator, attributed wuxia’s appeal to its novelty and the fact that historical and fantasy genres are most effective at introducing ideas from another culture.

“People are looking for something new, and Chinese sci-fi and wuxia fantasy are stepping into this void,” she said.

Thriving online

Unusually wuxia, though available in print, exists primarily online. Web stories have seen a surge of interest in China in the past decade ̶ and by far the most prominent wuxia website is Wuxia World.

Founded in 2015 by Chinese-American Lai Jingping, a former US diplomat, WuxiaWorld offers hundreds of free-to-download English translations of wuxia novels.

Jingping, who grew up in the US, fell in love with wuxia in his teenage years after watching a classic Hong Kong wuxia drama series, The Return of the Condor Heroes.

Unable to understand either the Cantonese dialogue or the Mandarin subtitles, he decided to learn Chinese while studying for a degree in international relations at university. Later, while working as a US diplomat, he began translating wuxia novels into English and posted them on a forum, where eager readers encouraged him to continue.

Jingping, who translates under the pseudonym RWX, eventually gave up his diplomatic career to concentrate on developing WuxiaWorld and the site now receives about two million visitors each month from over 150 countries.

Like most wuxia websites offering translated stories, the novels on WuxiaWorld will remain free for now, with the website relying on the advertising business model and donations from generous fans to stay afloat. But paywalls may be introduced in the future.

China is the hot ticket

It might be the case that wuxia novels are riding a current wave of interest about China.

According to Lu Cairong, deputy director of the CIPG (China International Publishing Group) there were more than 20,000 books about China published in English in 2017 – a number that doubled to 40,000 last year.

Whether it’s the “Brexit effect” of actively looking beyond Europe for our cultural sustenance or simply a desire to leap on a new trend, China these days seems far from the faint blip on our radar it used to be.

And with China’s relationship with the West an often fractious one, perhaps an increased familiarity with Chinese culture could help oil the cogs of diplomacy and bolster cultural ties in the future.