𝘈𝘱𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘹 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦: 6 𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘴🕒

“I didn’t know that Japanese novels are that popular in Britain. What’s the reason? I have no idea. Maybe you could tell me – I’d like to know,” Haruki Murakami told the Guardian.

We will try our best, Haruki.

And I’ll be honest, I like books. I like books a lot (speaking as the writer).

But until Wolfestone’s Head of Marketing, Keiran Davies, was explaining the depth of translated novels from East Asia to the UK, I wasn’t previously aware of this trend.

So, what has caused this rise of Japanese and Korean translated fiction?

Simply put, there are a few factors all marrying up together at the same time, including a fascination of East Asian themes, an award win, ‘BookTok,’ and more.

In this blog, we will dissect these ideas in more detail, and analyse the forms of translation used, and why.

It’s not an entirely new idea

The man I quoted, Haruki Murakami, is somewhat of a legend in this game. He had his first book, ‘The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle’, published in the UK by Harvill Press in 1998.

So too is Banana Yoshimoto. Her books were translated into English in the late 80s and 90s.

Despite translated East Asian fiction being enjoyed almost four decades ago, it didn’t really take off to this extent of popularity until the last five years or so.

An industry on the rise

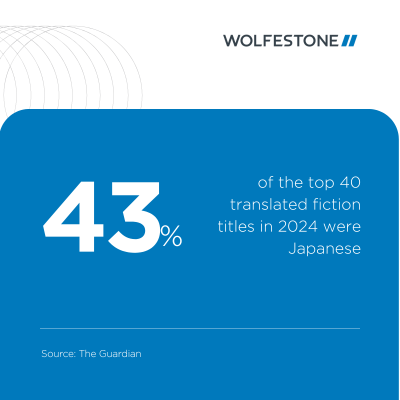

Beyond having dedicated tables to Japanese and Korean translated fiction in Waterstones and the like (other book shops are available) over the last year or two, the figures certainly back-up the uptake in the genre.

Data from the Guardian shows that almost half (43%) of the top 40 translated fiction titles in 2024 were Japanese.

As for Korea, literature sales abroad more than doubled from 520,000 in 2023 to around 1.2 million in 2024, figures from the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea) outlined.

Between 2020 and 2024, 942 titles spanning 40 languages sold 2.68 million copies. That figure rose 730,000 from the previous five-year period (2019-2023).

What is interesting to note though, is that it’s not just new books that are causing the uptake in literature. For example, the number one spot for Korean fiction for the first half of 2024 was Contradictions by Yang Gui-Ja, published in 1998 and translated in 2005. Demonstrating that the rise includes a mixture of new releases and older novels.

This resurgence of interest in both contemporary and classic titles points to a deeper shift. Readers in the UK are exploring a wider catalogue of fiction, driven by curiosity and a fascination with Korean and Japanese culture.

At the same time, publishers have become increasingly more willing to take risks on translated works, backed by clear evidence and market research that there is a sustainable, growing readership in the UK.

Fascination with cultures

From the outside looking in, there is a general fascination with East Asian cultures and perhaps by reading these translated novels, readers can better understand this.

They cover topics that aren’t touched on so much in the UK, such as historical traumas, the fragility of human life, and experiences that can only come from East Asia. Perspective is considered, too.

“In Japanese fiction, readers are finding comforting stories about ordinary lives transformed by small adjustments of attitude, suggesting positive change is something we can all reach, if we are open to it."

The translated novels also tap into the idea of escapism through the ‘cozy fiction’ genre, also known as ‘healing fiction’, or ‘cat fiction’. It surrounds cats, coffee and bookstores.

For many readers, translated Korean and Japanese novels provide a way of exploring social values, culture and philosophies that may differ from more ‘Western’ narratives, such as intergenerational relationships.

Ultimately, a novel set in Tokyo or Seoul is grounded in a culture that, in many aspects, can be very different from the UK. However, having said that, human emotions and other themes resonate across borders.

Leveraging language solutions

The actual process of taking East Asian fiction and translating it into English is often understated.

It’s not done at the click of a finger. We’ve been in the translation and localisation industry for 19 years now, and we can tell you that from experience.

Not all of the content in the books is directly translated either. Some sentences may not make sense when they were translated over or wouldn’t align with expectations in that country, in terms of repetition, cultural differences and more.

That’s where literary translation and transcreation come in – translation done creatively to ensure the copy still holds the same impact and meaning in another language.

For example, a transcreator notes that “in Japanese (news) writing, it often seems that if something is worth saying, it is worth saying more than once… But there’s definitely a contrast with the emphasis on brevity in English-language journalism.”

Multilingual Desktop Publishing (DTP) also plays its part, as not all languages are in in the same script, and not all words have the same length.

Translating Japanese into English can make the text 20% - 60% longer. Part of the reason Japanese is shorter can be attributed to the use of ‘kanji’, symbols used in Japanese writing. These characters can typically display a ‘thing’ or a concept. So, to transcreate that into English, it would take more words.

As for Korean, it tends to be a bit shorter than English writing. That is because in Hangul (Korean alphabet), writing blocks are used to indicate syllables, whereas in English, every syllable is spelt out.

In English, ‘I love you’ takes up eight characters, including spaces. On the other hand, the Korean version: ‘사랑해’ (saranghae) is just three characters.

So, naturally, translated books into English will be longer as a result.

Nobel Prize win by Han Kang

Han Kang’s Nobel Prize was said to be a “decisive catalyst for Korean literature’s global reach”, according to LTI Korea.

Having looked at the stats, we can agree.

- Han’s works were translated into 28 languages

- They were published in 77 editions

- Her work sold around 310,000 copies in 2024 alone

- Annual overseas sales of her work rose by five times – around 30,000 sales in 2023 to 150,000 in 2024

Following the win, there was so much traffic that the websites of two of South Korea’s biggest online bookstores crashed, The Korea Herald reported at the time.

We can all agree that Han Kang’s recent success has not only put South Korean literature on a pedestal, but it has also meant that translated Korean literature is even more sought-after than before.

‘BookTok’

For those not on social media - yes, this really is a thing. And, in my opinion, it’s played its part in the rise of these books. Discussions, previews, and more on social media video platform TikTok have helped raise the profile of the genre.

Some teasers of Japanese translated books, like ‘She and Her Cat’, have garnered more than 40,000 likes on TikTok.

This is important to note because it opens up the novels to a new type of consumer. Typically, Gen Z aren’t reading detailed book reviews in newspapers, but they may be on said BookTok looking for a quick snippet as to what to read next and why.

Visual content, such as short-form videos, has been shown to boost engagement (through likes, shares, comments and click-throughs) as opposed to text-only posts.

While we touch on Gen Z and TikTok, it is worth mentioning that it is also readers in their 20s who are ‘driving energy to bookstores’.

In 2022, Nielson research showed that readers sub 35-years-old were responsible for purchasing nearly half (48.2%) of all translated fiction in the UK. They have been aptly referred to as ‘Generation TF’.

Their enthusiasm for books – and for sharing that enthusiasm online – triggers others to do the same, and this feeds into the desire for more East Asian translated novels, as a result.

Conclusion

It has been genuinely fascinating to find out more and more about Japanese and Korean translated fiction and I’m curious to see how the novels continue to force their way into the top-selling book charts.

Hopefully Haruki now knows why Japanese and Korean novels are so popular in the UK.

Key takeaways

- It’s not something entirely new

- However, in the last few years the pull of translated Japanese and Korean novels has been rising higher than ever before

- It’s been caused by a combination of the fascinating nature of East Asian culture and themes, clever use of language solutions, a boost from a Nobel prize win and ‘BookTok’

Contact us today to find out more about our language solutions such as transcreation and multilingual DTP.

𝘑𝘢c𝘬 𝘸𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘴 𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯, 𝘭𝘰𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘪𝘴𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘭𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘶𝘢𝘨𝘦 𝘴𝘰𝘭𝘶𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘞𝘰𝘭𝘧𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘯𝘦. 𝘏𝘦 𝘭𝘰𝘷𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘰 𝘧𝘪𝘯𝘥 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭-𝘭𝘪𝘧𝘦 𝘦𝘹𝘢𝘮𝘱𝘭𝘦𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘴𝘰𝘭𝘶𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦𝘯'𝘵 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘬𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦 𝘢𝘴 𝘮𝘶𝘤𝘩 𝘳𝘦𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦, 𝘰𝘳𝘪𝘨𝘪𝘯𝘢𝘭 𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘢𝘶𝘥𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦 𝘢𝘴 𝘱𝘰𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘣𝘭𝘦.